"Threadless Corner" -- JEPTHA WADE Part Two

by Ray Klingensmith

Reprinted from "INSULATORS - Crown Jewels of the Wire", October 1978, page 16

Since writing "Part One" on Jeptha Wade, I've

done a little more research on his life, coming up with even more information

than I expected. Also, with the help of some generous collectors, I can put

together a halfway decent representation of his insulators. Following is the

additional info, which at times may be a partial repetition of the first part. I

felt it should be included to give a clearer picture of this great man's life.

Jeptha H. Wade was the son of a civil engineer and surveyor. His father died

while Jeptha was still at an early age. As stated before, he became a carpenter,

and besides that, he also made clocks and musical instruments. When he was

twenty-one years old he owned a large sash and blind factory. That was his

occupation until he was twenty- four, at which time he became a portrait painter

under the direction of the famous Randall Palmer. Later he also became

interested in the daguerreotype, and is said to have made the first of that type

of "picture" west of New York City. At age thirty he settled temporarily in New Orleans. After becoming interested in the telegraphic field, he moved

to Detroit and entered into the telegraph business as described previously.

Wade

and John Speed were linked closely together in their early telegraph years, and

they consolidated each of their networks of telegraph lines to form the

"Speed & Wade Telegraph Lines" which consisted of 2,515 miles of

lines. There were 104 offices serving Buffalo, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Columbus,

Milwaukee, St. Louis, Pittsburgh, Warren, Wheeling, Zanesville, and various

other cities and towns. Headquarters was in the American House in Cleveland. On

April 4, 1856, thirteen competing telegraph companies operating lines in five

states north of the Ohio River merged into the Western Union Telegraph Company.

As near as I can gather, Wade moved to Cleveland, Ohio, in 1856 to become

general agent of the newly formed company. He became very much involved in the

field of telegraph, and in crossing the Mississippi River at St. Louis with

one of his lines, he became the first person to use a submarine telegraph

cable. In 1867 he became seriously ill and for some time could no longer

continue in his work.

In later years he became very much interested in

benefiting the city of Cleveland. Following is a partial listing of his

activities:

- On November 9, 1863, the Cleveland Rolling Mill Company was formed, with Wade

as one of the incorporators.

- President, The Citizens Saving & Loan

Association, organized August 1, 1868.

- Part owner of the Cleveland & Newburgh Railroad Company, which began

operation on October 20, 1868.

- Brooks School, a college-preparatory school for

boys, was opened in 1875 with financial aid from Wade.

- The Euclid Avenue Opera House was opened on September 6, 1875, after many

financial barriers had been overcome, on financial aid from Jeptha Wade.

- He owned approximately 75 acres of land, and for many years had been allowing

the public to use it as a park. In later years, the Cleveland Museum of Art was

built on part of his land.

- On September 25, 1882, City Council accepted as a gift from Wade a tract of

land fronting Euclid Avenue to be used as a park.

- President, Valley Railway Company.

- Director, Second National Bank of Cleveland.

- Director, Cleveland Iron Mining

Company.

- Director, Union Steel Screw Company.

- President, American Steel and Boiler Plate Company.

- President, Chicago and Atcison Bridge Company.

- City Park Commissioner.

- President, Kalamazoo, Allegan and Grand Rapids Railroad.

- President, Cincinnati, Wabash & Michigan Railway Company.

He also was instrumental in the formation of many charity groups, and donated

large amounts of money to various groups for many years.

He had at least two

sons: Randall P., whose house appears on the following page with that owned by

his father; and Jeptha H. Wade II, who in turn named a son Jeptha H. Wade III.

(The name of the son Randall P. brings a question to my mind. Was his middle

name Palmer? Perhaps he was named after the famous artist under whom Wade had

worked in his early life.)

On August 9, 1890, Jeptha Wade died in Cleveland. He

was an ambitious individual, both in business and in social life. His mark on

Cleveland will remain forever, through his many generous donations to that city.

Now that we have some background information on Wade, let's get into the study

of his insulators. Included are many "Wade type" insulators which may not

have actually been a product of Jeptha Wade. Some of them were made for and used

by other telegraph engineers and companies. When using the term "Wade

type", I'm

referring to the glass insert type threadless, designed to be used with a wood

covering or shield. Exactly where to start with the drawings and photos is a

real problem. Due to the fact that there isn't any information on the actual

production of the different types, it leaves me with one word - Help!

I cried

for help, and it came primarily from two different sources. Jack Hayes was very

helpful with drawings, photos, and info on the "Canadian Wades"; and

the Plunketts, who have labored long hours in collecting these jewels, came up

with much of the same type of greatly helpful information.

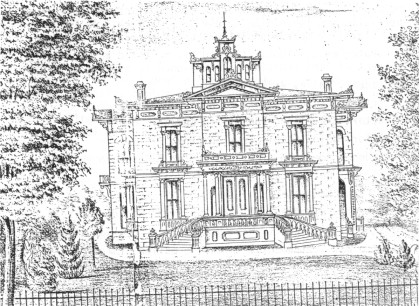

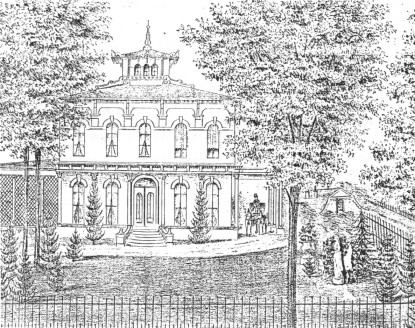

Home of R. P. Wade, son of Jeptha H. Wade.

Jeptha Wade home as it appeared in 1874.

Basically, there are

two categories which can be used to classify the Wade type threadless -- those

known to be used in Canada, and those known to be used in the United States. I

feel that both types are equally desirable and share the story of the telegraph

in the same way. Due to the fact that Wade was from the United States, I'll

cover those types first. On the following page is a copy of a page included in

"History, Theory, and Practice of the Electric Telegraph". (Frank

Jones, Cottontown, Tennessee, made reprints of this book in 1972, which was

originally printed in 1860. He included five pages from another book printed in

1874 on line insulation, which is where the "Wade" was shown.

Anyone who doesn't have a copy of Frank's reprint should contact him. It

certainly is worth reading.)

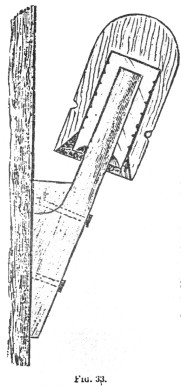

Fig. 33. |

93. The Wade Insulator. -- This is largely

used in the Western States. Its construction is show in Fig. 33.

A glass insulator, somewhat similar in shape to that last described

is covered with a wooden shield, to prevent fracture from stones and

other causes, the wood being thoroughly saturated with hot coal tar, to

preserve it from decay. The line wire is tied to the outside of the

shield in the same manner as when the glass insulator is used.

This insulator is usually mounted upon an oak bracket as in Fig. 33.

secured by spikes to the side of the pole or other support. When it is

intended to be mounted upon a horizontal cross-arm it is placed upon a

straight wooden pin instead of a bracket. The pin or bracket is usually

saturated with hot coal tar in the same manner as the insulator shield. |

This drawing and printed material, from an 1874 book, shows the manner in

which the Wade type insulator was constructed.

- - - - - - - - -

There are basically five types known to have been used in the United States.

Fig. 1 shows the "smooth" type. It is reported in the following

colors: aqua, light aqua, dark aqua, and cobalt blue. (I've seen two of

the cobalt ones. As near as I can remember, one was a little darker than the

other.) This type may have been the first style manufactured, the others

being "improvements". The Plunketts report that "Unlike the

dot-dash, all of these seem to be the same size."

Fig. 2 shows the "concave Wade". This is a rough sketch of this

item. I saw it at a show last fall, and it may be one-of-a-kind. Steve Bobb

(Pa.) owned it. Anyone have another? The color of that one was aqua.

Fig. 1 Smooth Wade. |

Fig. 2 Concave Wade. |

Fig. 3 Dot Dash Wade. |

Fig. 4 Chester type. |

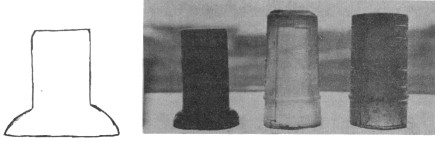

Fig. 5 The Chester type, dot-dash, and smooth Wades.

Three styles used in the United States.

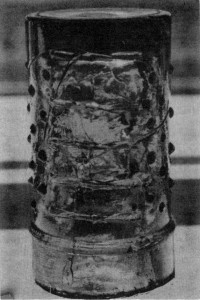

Fig. 6 Base view of the dot-dash type, showing the two

different types of pinholes. On the left, "blown" variant.

On the right, pressed variant.

Fig. 7 Wood covered Wades.

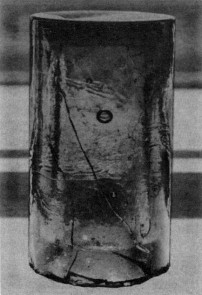

Fig. 3 shows the 'dot-dash' type. These were widely used in most parts of the

country. I know of their use as far east as Pennsylvania. From there they were

used westward all the way to California. These more than likely were produced by

several different glass houses over a period of years. I've examined some with a

one inch threadless pinhole, and some which appear to have been

"blown" into a mold, rather than "pressed" with a plunger.

The appearance of the interior of the 'blown" units is rather unusual. The

interior surface seems to follow the outline of the exterior surface. Wherever

there is a dot or dash on the outside, there is a depression on the inside. It

looks like air pressure formed the inside, the glass following the shape of the

mold, all at the same thickness. I've examined a few of these items with parts

of the original pins still in them. One had a wooden pin which was wrapped with

a type of material similar to burlap. This covered pin was dipped in what

appeared to be plaster of Paris, and the excess white material had filled the

depressions I mentioned earlier. This certainly looked like a "glued on

affair" and certainly was interesting. If it had not been for the insulator

lying on the ground for over 100 years, I'm quite sure the pin and insulator

could not have been separated.

The "dot-dash" comes in a variety of different heights. Some have

the bottom "ring" closer to the base than others. The Plunketts report

heights from 3-3/4 to 4-5/16" tall, and dots and dashes more pronounced on

some. They are reported in aqua, light aqua, blue, light green, very light green

(almost clear), celery green, and -- grab your hats folks -- medium amber!

That's a real dandy!

Fig. 4 shows the "Chester type". Some of these are embossed on the

base -- Chester N.Y. The embossed item comes in a beautiful cobalt blue. At the

present that's the only color I can recall in that one. They also come

unembossed, and are reported in aqua, lime green, and (if I'm correct) the

unembossed comes in cobalt also. There is one in pink. Yes, it's really

pink! For those of you who are familiar with "Depression glass", it is

very similar to the color in some patterns of "Depression". It has a

very slight orange tint to it. For those of you who can't believe it -- I saw it

once, and then started to wonder if I was OK that day! On a recent trip to New

York State, I was very happy to be the guest of the Bowmans, where I could view

that rare jewel once again. Believe me, it's real!

Fig. 8 shows an unembossed unit, with a different base than fig. 4. It is a

beautiful lime green, and may be one-of-a-kind.

The Wade types used in Canada are in many ways similar to those used in the

United States, but have unique characteristics also. Fig. 9, 10, 11 shows from

left to right: "Canadian Chester", "Baby Wade", variant two,

"Baby Wade", variant one. Before I go any further on the three items

in the Canadian group, I feel it would be best to use some quotes from letters

written to me from Jack Hayes. I will use parts of his interesting and

well written information.

"I found pieces of small Wades at the Canada Glass Company site, Hudson,

Quebec, which operated between 1862 or 3 to 1874. The company made druggist

bottles. As stated in an 1867 Montreal Gazette article, 'the operations, which

at first were limited to the manufacture of druggist bottles and telegraph

insulators, etc., have recently much extended to lamp ware and German Flint

Glass.' A book by Hilda and Kevin Spense of Hudson, Quebec, shows coloured

pictures of druggist bottles in red and blue. Also, we picked up pieces of the

fire brick from the site with plum red, cornflower blue and other coloured glass

attached."

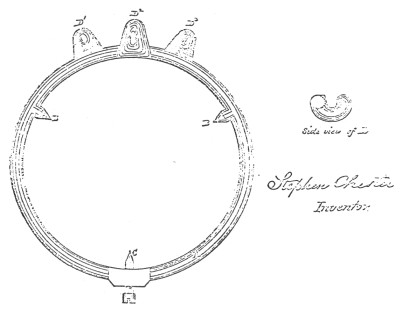

Fig. 12 1871 Chester patent drawing. The three lugs or

fingers held the line wire, and therefore eliminated

the need for a tie wire.

A nice group of Wades.

A wood covered Wade, and a Chester type with

what may be a "fingering ring" on it.

Fig. 8, 9, 10, 11. Unembossed lime green, Canadian

Chester, baby Wade with tapered top, baby Wade.

In referring to the "Chester type", Jack stated: "A magazine

at the time Chester began in 1855 wrote, 'The following engraving represents a

modern shield insulator by Charles T. and J. N. Chester of New York.' It showed

a wooden shield over a glass insert with an iron ring firmly pressed on it to

hold the wire without a tie wire. The size of the wooden shield is 4" in

diameter and 6" high. The glass is 2" by 4". According to the

Chester catalogue, the glass part was sometimes used without the shield. In 1861

you could buy them for $.20 each or $.25 with the iron ring. They sold very well

and were used for over ten years, but proved to be poor insulators when wet and

were difficult to check for breakage. In 1871 a younger brother, Stephen,

patented a modified version of the ring.

"I have hopes that the small Chester type found in Canada will turn out

to be of Canadian manufacture. It is interesting that the small ones have been

found only in Canada (all in southwestern Ontario) and the big ones only in the

United States. The manufacturer (of the small ones), I believe, will turn out to

be Hamilton Glass Works: but this is only based on the appearance, i.e., when

looked at from the bottom you cannot tell it from the Baby Battleford which was

made at Hamilton (again, based on finding an aqua Battleford at the Hamilton

site by a contractor digging for foundation construction). All of the small

Wades are two piece molds with a pin pressing the hole.

"I mentioned the small Wades being found only in southwestern Ontario,

but they were no doubt more widely used. I have pictures of Ottawa with

telegraph in 1855 to 1875. One has a pole with four crossarms and 13 insulators,

all of which I am certain are Wades (small)."

Thanks, Jack, for all that info!

With all the color variations in the nine styles, we have a total of about 30

different ones to look for at the present! Time certainly will reveal a few

more. So with that in mind, an end must come to this story on Jeptha Wade.

Although the article must end, his influence on the world will survive forever.

For photos and drawings and a great amount of help, a big THANKS to

Jack Hayes and the Paul Plunketts of St. Charles, Illinois. For describing color

variations, thanks to Dick Bowman, Fred Griffin, and Bob Pierce. Thanks also to

Frank Jones for his efforts in getting "History, Theory and Practice of the

Electric Telegraph" reprinted; to the Roosevelts of Elyria for getting

copies of the Wade homes; and once again to the Branhams of New Jersey for

patent research.

|